Today's post is brought to you by a five day vacation, during which I've been catching up on some reading and not working long hours! I've found a couple interesting pieces recently on the subject of why people burn out, which suggests it's not the overtime in itself.

The first article was on Blogher, It's Not Just You. A recent Wharton School study looked at reasons for worker burnout. (It's unfortunately not yet available free online.)

"One of the biggest complaints employees have is they are not sufficiently recognized by their organizations for the work that they do. Respect is a component of recognition. When employees don't feel that the organization respects and values them, they tend to experience higher levels of burnout." Or, as Ramarajan puts it, "it is often not the job that burns you out, but the organization."

It turns out there was another good piece in the NY Magazine, Can't Get No Satisfaction, which meanders through social worker burnout, teacher burnout, medical burnout, and into high tech and NY Wall Street burnout. This one notes previous good research:

In 1981, Maslach, now vice-provost at the University of California, Berkeley, famously co-developed a detailed survey, known as the Maslach Burnout Inventory, to measure the syndrome. Her theory is that any one of the following six problems can fry us to a crisp: working too much; working in an unjust environment; working with little social support; working with little agency or control; working in the service of values we loathe; working for insufficient reward (whether the currency is money, prestige, or positive feedback). “I once talked to a pediatric dentist,” she says, “and he said, ‘A good day is when there are no screamers.’

Googling for Maslach, I hit an online quiz that rates your current level of burnout risk. The questions are about how you feel and about your work environment, as predicted by Maslach's findings. (E.g., "Do you feel that you are achieving less than you should?"; "Do you feel under an unpleasant level of pressure to succeed?"; "Do you find that you do not have time to plan as much as you would like to?" etc.) See how you score!

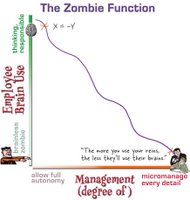

Finally, there's a related by different piece I just read when catching up on Creating Passionate Users, on Knocking the Exhuberance Out of Employees. When you burn people out, you've got robots and zombies working for you. Zombies and robots don't argue, don't have ideas, and don't threaten you or the status quo. They're a lot easier to manage, too. Hopefully no one who works for me is reading this, though, because I like arguing with them and am in no way an advocate of less exhuberance. Let that go as read!

Lastly, an article on Job Burnout in an online manufacturing magazine says (citing Maslach) burnout is about a mismatch "between what people are and what they have to do. It represents an erosion in values, dignity, spirit, and will-—an erosion of the human soul." America, with increasingly long hours and questionable corporate values, is a leader in burnout. We measure customer satisfaction, but worker satisfaction isn't a serious corporate issue, and the 40 hour work week is long dead.

Postscript: I can't believe I forgot the classic article on burnout, the electrocuted dogs experiment by Seligman: Learned Helplessness. This one has a positive spin to it, in that it suggests some therapeutic ways out of the syndrome. Happy New Year!